Shark Deterring Stickers

Sharks and Surfers in Australia

The harsh reality is that far and away, the main problem that Surfers in Australian waters have been encountering with sharks, relates to interactions with near mature or mature in size and age (+3m), Great White Sharks. Although more rarely there are encounters with other large, potentially deadly species such as Bull Sharks and in generally warmer water settings, Tiger Sharks, it’s the Great Whites that pose the most threat.

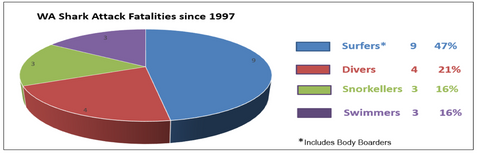

It’s a modern trend that we estimate commenced in the late 1990’s and is continuing today as highlighted in the Graphics below. This shows the clear trend that has emerged in WA, where there is most data (refer graphic derived from WA Fisheries Report No. 273, 2016). In this period, aggressive incidents between Great Whites and Australian ocean users, particularly Surfers, has escalated at a rate significantly in excess of our population growth (refer graphic derived from WA Fisheries Occasional Publication 109, Nov 2012).

Published statistics show clearly that Surfers are the most attacked demographic group. But, conversely, Surfers have the highest survival rates for Great White attacks. Mainly because in many cases our Boards just get in the way!

Further, there is mounting evidence about how selective attacks by Great Whites are in terms of Where, When and even Who.

The How is almost universally via an ambush attack, hitting the victim from their blind spot. For Surfers the data shows this is usually from behind, below and the shoreward side while they are focussed outward on where their next wave is coming from.

What to do?

Various agencies are working on attack mitigation strategies that range from netting off beaches to innovative, new technologies which it is hoped will prove to be effective deterrents, protecting coastal water- users generally.

But of course these agencies simply cannot be resourced to have oversight on every piece of our vast coastline. Including the many isolated and unique spots that Surfers love to get to.

At present we see the mitigation methods falling into 3 main categories:

- The positioning, near selected locations along the Coast, of Transponders that can detect the presence of tagged sharks that then link to physical or automated warning systems;

- Various measures designed to get a visual on the approach of sharks to public in-water use areas (like helicopter and Drone overflights or Surf Live Saving observer posts), again primarily linked to warning people out of the water and:

- Devices like the Shark Shield that are promoted as providing individual based mechanisms to deter attacks by sharks.

At Mazorca we believe that:

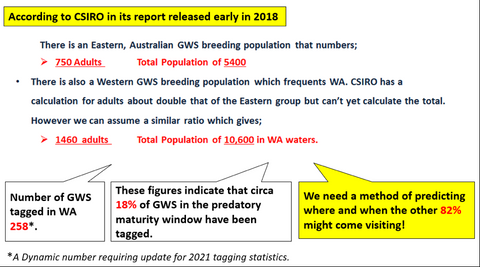

- Unfortunately there is only a small proportion of the Great White Shark population that has been tagged and can set off a Transponder. In the Figure following we try to illustrate the statistics behind this;

- It’s just not possible to have effective aerial surveillance coverage over all of our vast and varied coastline and;

- It simply makes sense to have more than one personal protective method in play to manage one’s own risk in the water.

So accordingly, our focus at Mazorca is on promoting thinking about and development of low cost initiatives and products that can contribute to individual Surfer safety and peace of mind.

We have started with our King Cobra transfer (see below) to be used underneath your board that in part draws inspiration from Hawaiian culture and is fundamentally about sending a warning to a predator (shark) that might otherwise consider an attack.

In this same line of reasoning we are working on another low cost deterrent measure that we hope to release in 2022.

You might combine these measures with a simple action while in the line-up that has been suggested to us by John Begg, principal of our co researcher Rock Doc.

We call it the FinSpin. Instead of sitting on your Board in the line-up at a habitual, set angle, looking seaward for your next ride, try going through a regular back and forward rotation covering up to 225°. The idea is to minimise your position with a set blind spot, therefore weakening the prospects for an ambush attack.

(Research contributing to this section of our website has been prepared with the assistance of Rock Doc Pty Ltd).

Some Further Background

Sharks generally possess an impressive array of highly specialized sensory systems that all experts tell us have been shaped over millions of years of evolution. Many sharks are thought to rely on their visual system for prey detection, predator avoidance, navigation and communication. Sharks use vision particularly in the final approach to prey (Gardiner et al., 2014) and a number of behavioural experiments have demonstrated the importance of vision in prey detection and capture (Gilbert, 1963; Fouts and Nelson, 1999). Many sharks exhibit both behavioural and morphological adaptations that aid in the detection of prey. For example, white sharks, (Carcharodon carcharias) are thought to be a predominantly visual predator and possess many behavioural and visual characteristics that enhance detection and capture of prey above them (Gruber and Cohen, 1985; Strong, 1996; Litherland, 2001; Hammerschlag et al., 2012). Sharks will attack non-prey items on the surface of the water-based primarily on the visual cues of the silhouette (Anderson et al., 1996; Strong, 1996; 3). Underwater observations suggest that Great White Sharks rely on vision to orientate towards the target, and in clear water this occurs from as far as 17 m away from prey (Strong, 1996).

A sharks perception of prey is defined by many aspects such as their ability to detect colour, shape and motion (Eckert and Zeil, 2001; Land and Nilsson, 2012). The abilities of sharks to discriminate light of different wavelengths and their anatomical and physiological adaptations for increased absolute sensitivity have been relatively well studied (Gruber et al., 1975; Litherland et al., 2009; McComb et al., 2010; Hart et al., 2011; Schieber et al., 2012; Kalinoski et al., 2014). Sharks have monochromatic vision meaning they only have one spectral type of cone as well as one spectral type of rod. Mounting evidence that sharks are colour blind (Hart et al., 2011; Schluessel et al., 2014). Black and white contrasts are intended to mimic the banded poisonous sea snakes, which many sharks appear to avoid (Doak, 1974; Nelson, 1983; SAMS, 2013).

As we discussed earlier, Apex predators rely heavily on the element of surprise. Mimicry (large false eyes) is displayed heavily in the wild to remove the element of surprise. The KingCobra replicates this natural form of defence in combination with the contrast of black and white stripes. This creates visual confusion to the sharks and changes how the board is perceived. Many sea creatures have evolved to take advantage of this same colour pattern, many of which are poisonous. This suggests that black and white stripes act as a warning to sharks. The ‘King Cobra’ snake alters board appearance, intimidates, looks dangerous and influences a shark’s instinctive strike behaviour. Enhancing Biomimicry to mitigate shark risk is a low-cost environmentally friendly approach, although not guaranteed will provide an extra layer of potential defence for ocean users.

If you want to look scary, be scary!

The ‘King Cobra’ is purpose-built, non-invasive, looks great in and out of the water and is affordable for all ocean users.